| While the instruments are genuine in

this picture, this medical cane was been put together recently. Many

similar fake canes seem to be coming out of England. |

|

| This was said to be a physician's

pharmacy thermometer cane, whatever that might be. It is a

modern fake. |

|

| A pewter bottle with spurious Confederate

hospital markings. |

|

|

A pewter canteen with bogus engraving indicating ownership by a

well-known South Carolina Civil War surgeon.

|

|

| Another fake Confederate medical item. Several of these

canteens have appeared recently. Unless you are an

expert in mid-nineteenth engraving and other marks, avoid any such items. |

|

|

So-called medical

chewed or pain bullets are mis-identified. An easily swallowed bullet is the last thing

that one would want to put in the mouth of any anxious patient. To bite the bullet is not

a medical phrase, rather it is an old military term referring to loading a

muzzleloader. The tip of a preloaded ball and powder paper cartridge was

opened with the soldier's teeth, the powder and ball were then poured into the

muzzle, the paper cartridge, itself, came next as packing, lastly, all was

tamped down with a ram rod. In the heat of battle, it is possible that

soldiers may have bitten the paper cartridge at the wrong end (bullet

end) and this may have caused some of the marks.

|

|

|

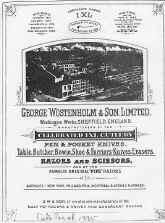

Nineteenth century ink erasers and quill

sharpening knives are often

sold as Civil War scalpels or bleeders. A commonly seen maker

is Rodgers, a Sheffield cutlery firm. While Rodgers did make a veterinary

fleam, I have never seen any surgical instruments from them. Note also

that handles identified as ivory are often made from a celluloid commonly called

French ivory or ivorine, which was introduced in the 1870s

Another ink eraser offered as a Civil War period

fleam/knife. It was made by Miller Brothers Cutlery Co., Meridan, Connecticut.

|

|

| The Wostenholm catalogue of c.

1885 illustrates and describes various ink erasers and office (quill) knives.

Many cutlers made who such instruments were based in Sheffield. |

|

| A c. 1900 manicure knife offered as a

Civil War scalpel. |

|

| A nineteenth century photo of a railroad

field hospital mis-described by the seller as a Civil War field hospital.

The scene is identified on the back as: Surgical Ward Field Hospital

N.P.R.R., Dr. R. H. Littlefield, Surgeon and Davidson's Views of

the Pacific Northwest embracing Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. |

|

| A common hydrometer that was offered as a clinical thermometer

made by Reynders of New York. Note that the case with the Reynders trade

label is not original to this hydrometer; the fit is not correct. A maker

attribution by the case alone, as in this example, can be problematic. |

|

| A reproduction and over-the-top doctor's sign offered as an

antique. Signs of this fanciful type appear to be coming out of

England. Similar signs celebrate lawyers, accountants, etc. |

|

| Another problem sign for the medical collector is this

nineteenth century fraternal all-seeing eye that was offered as an eye doctor's

trade sign. Think eye as on the one-dollar bill. |

|

| A small mallet with horn head that was described as an early to

mid-nineteenth century reflex hammer. It is not a reflex hammer, but it is

a dental mallet that was used to hammer rubber and acrylic dentures out of

the stone beds of the cuvettes. This type of mallet was in general use until c.

1970. |

|

| A reproduction microscope offered as an antique made by Philip Carpenter, London,

c. 1826-1833. This replica instrument was made and sold, initially, as a

decorator piece. |

|

| A child's microscope, commonly called a boy's

microscope, made in France and ubiquitous in the later part of the

nineteenth century, but offered as a rare Civil War medical corps

microscope. |

|

| Here are some mid-nineteenth century

autopsy instruments by Matthews, London, which were described by the seller as

military field surgeon's amputation instruments. Note the costotome (rib

shears). The use of the term field surgeon is carelessly

bandied about...usually as an attempt to hype an item as being from the

American Civil War. |

|

| This group of bone-handled instruments was called a pre-Civil

War field surgeon's set. These are certainly not surgical

instruments. The ink eraser, the second piece from the right, is marked FABER

and GERMANY. Faber was and is a German maker of writing

instruments. Generally, any instrument that is marked with the country of origin

will date to post-1890. |

|

| This outfit was described as a Civil War amputation set wooden case.

The carved wooden case is a medical fantasy and the ether tin dates to post

1900. A pocket knife was put forward as the amputating instrument. |

|

| A common c. 1880s medical student's dissecting set offered as a

Civil War bullet extracting set. While there are specialized bullet

extracting instruments (none seen here), there is no such thing as a bullet

extracting set. |

|

| This is an item mistakenly called a Civil War field

medical kit. It is a canvas minor veterinary surgery wallet from

post 1900. The top instrument was used for cleaning the hooves of

horses. A manicure nail cutter is also present and may be an add-on. |

|

| This medicine case was described as a Civil War doctor's medical

kit. The snap closure, which first appear on medical cases in 1890s, and the

leatherette material of the case tells otherwise. Also, the style of

printed lettering on the bottles is a post Civil War style. |

|

| Numerous examples of this sort of chair

are in the market. They are usually called birthing chairs.

I suspect that they are made for the South American tourist market . |

|

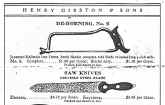

This

is a rather common late nineteenth to early twentieth century butcher's

combination saw knife. Unfortunately, this saw has made it into Francis

Lord's Civil War Collector's Encyclopedia, Vol. IV, p. 122, where it is

described as a Civil War amputation saw/knife. One

point to keep in mind when it comes to saws is that a capital amputation saw

blade of the tenon type must have a spine to keep the blade rigid. A blade

that wants to buckle presents problems. Also, the quality of the saw is

not up to the level of surgical saws. Some of these saws will be marked US.

These marks mean

that the saw was government property and, for example, to be used by a butcher

in the army.

This close-up of the saw knife shows faint US

marks.

The Disston hardware company was a major maker of the saw

knife. It last appeared in their catalogues in 1914 and was considered by

them to be in the butcher saw family. The catalogue page

here shows the saw knife listed between a dehorning saw and a paint scraper. |

|

| This

is a butcher's saw that was offered as an old surgery saw. The

saw does not have a spine and the quality is poor. (Note the description

of the previous saw.) |

|